Después de más de 10 del comienzo oficial del movimiento del acceso abierto, me pregunto porqué queremos que la literatura científica esté en abierto, porqué es tan necesario.

Stevan Harnard, uno de los más influyentes defensores del movimiento para el acceso abierto, en su artículo The optimal and inevitable outcome for research in the online age[1] dice que el acceso abierto quiere decir libre, online, y accesible en todo el mundo para la investigación y destaca que el propósito del acceso abierto es hacer la investigación accesible a los posibles usuarios, no sólo aquellos cuyas instituciones se pueden permitir la suscripción a la revista en la que haya sido publicada.

El movimiento para el acceso abierto comenzó oficialmente con la Iniciativa de Acceso Abierto de Budapest en 2002, como la primera en usar el término Acceso abierto con este cometido. Además aglutinó otros proyectos con el mismo objetivo que habían nacido a mediados de los 90: promover el acceso abierto a la literatura científica publicada en revistas.

Como bibliotecarios y documentalistas, especialmente aquellos que trabajamos en bibliotecas de ciencias de la salud, debemos tener clara nuestra misión en este movimiento y sus dos bien conocidas estrategias complementarias, el autoarchivo y la publicación en revistas de acceso abierto. Tenemos que enseñar a nuestros usuarios los beneficios de la publicación en acceso abierto y cómo encontrar revistas científicas de acceso abierto y cómo evaluar su calidad. También debemos mantener repositorios institucionales y promover entre los autores, el autoarchivo de sus trabajos de investigación publicados en revistas científicas.[2] y [3]

La difusión de la idea de apertura y transparencia y la conciencia de que los autores y revisores son los que proveen de contenido a las publicaciones científicas ha llevado a cuestionar mucho de los aspectos del tradicional sistema de publicación académica. El modelo de negocio de las revistas científicas, el proceso de revisión por pares, el sesgo en la publicación de los ensayos clínicos o el factor de impacto se han visto afectados, hasta el punto de remover sus cimientos.

Como Maria Kowalckzuk comenta en su post Are journals ready to abolish peer review?[4] el engaño de John Bohannon publicado en Science, el incremento en las retractaciones y el desencanto con las revistas más destacadas ha desencadenado una discusión sobre la validez del actual sistema de revisión por pares. Yo añadiría que la demanda de transparencia en torno a los ensayos clínicos y de la publicación de resultados negativos también tienen una parte importante en ello. De hecho ya han surgido diferentes iniciativas como: proceso de revisión por pares abierta (no anónima), algo especialmente crítico e importante para los ensayos clínicos[5], por ejemplo eLife, F1000 Prime, or Rubriq; revisión por pares por una plataforma y transferencia del manuscrito a la revista más adecuada entre las asociadas o consorciadas,NPRC Neuroscience Peer Research Consortium, Peerage of Science, Axios Review; y revisión posterior a la publicación, F1000 Research or PubMed Commons.

Con respecto al impacto y visibilidad de la investigación, el factor de impacto ha sido cuestionado desde hace tiempo, porque lo que fue creado como una herramienta de medición para evaluar y comparar las revistas científicas de una misma disciplina científica, se ha utilizado para evaluar los artículos que contienen. Por esta razón, están surgiendo nuevas métricas basadas en el artículo, en lugar de en la revista, como unidad.

Investigadores, como Randy Schekman, uno de los tres Premios Nobel en Fisiología o Medicina, se han hecho editores y han cogido las riendas y han creado revistas de acceso abierto como eLife. Estas revistas tienen como propósito ser una alternativa a esos aspectos viciados y criticados que deben ser cambiados en la publicación científica.

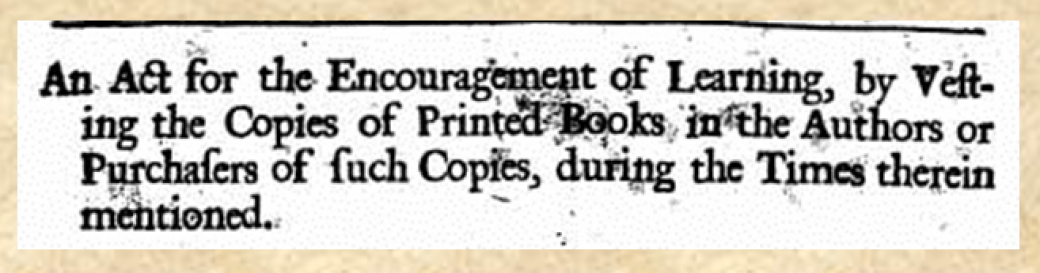

En todo este panorama cambiante, yo me pregunto porqué queremos que la literatura científica esté en abierto, porqué es tan necesario. Quizás parte de la razón esté en lo que John Willinsky nos recordaba en su deliciosa y amena conferencia What Is It About the Intellectual Properties of Learning[6]pronunciada en Varsovia en Marzo pasado. En ella, él nos trae a la memoria el Statute of Anne británico de 1710, considerado como la primera legislación sobre copyright otorgada en el mundo y destaca dos aspectos presentes en esta norma:

En primer lugar, el acta reconocía que los autores, como creadores de obras culturales, tenían ciertos derechos sobre impresores, vendedores de libros y otras personas que se tomaban la libertad de imprimir, reimprimir y publicar los libros sin su consentimiento. Con el fin de animar y proteger a estos autores, el acta les concedía una licencia exclusiva durante catorce años para copiar ese obra, en virtud de haberla compuesto y haber creado un bien público.

En segundo lugar, nueve copias de cada libro tenían que ser entregadas antes de su publicación para el uso de la Royal Library, las Bibliotecas de las Universidades de Oxford y Cambridge, las de las cuatro Universidades de Escocia, la del Sion College de Londres y la de la Facultad de Abogados de Edimburgo respectivamente[7]. Lo importante de esto, es que las copias debían ser colocadas donde pudieran estar accesibles para la gente porque el conocimiento tenía que ser protegido.

Por eso John Willinsky nos recuerda que la idea de propiedad intelectual está enraizada en el fomento y promoción del conocimiento, precisamente tal y como este acta se titula: ” Ley para el Fomento del Conocimiento, por concesión de los derechos de las copias de libros impresos a los autores o compradores de tales copias, durante los tiempos que en ella se mencionan”. Él declara que las Universidades participan activamente en la producción de conocimiento y por ello están en el centro del copyright, aunque, insiste, esta idea se está perdiendo y necesitamos recuperarla. Por esta razón él concluye: “Nosotros no estamos luchando por el acceso abierto en alguna especie de dispositivo técnico o estrategia técnica, nosotros estamos luchando por un principio básico que estaba en el mismo fundamento de la propiedad intelectual: para el fomento del conocimiento.”[8]

Pero hay un paso más. Muchos conocen la historia de Jack Andraka: el chico de quince años que ha desarrollado un test para la detección precoz del cáncer de páncreas usando tiras de papel, nanotubos de carbón y anticuerpos sensibles a la mesotelina. En una Ted Talk[9], él cuenta su experiencia tras la muerte por cáncer de páncreas de un amigo cercano de la familia cuando él tenía trece años. A través de Internet buscó información sobre esta enfermedad y se enteró de que en torno al 85% de todos los cánceres de páncreas eran diagnosticados tarde cuando las posibilidades de supervivencia era mínimas porque el test para detectarlos era muy caro y poco preciso. Buscó en Google y Wikipedia y encontró un artículo que relacionaba unas 8000 proteínas diferentes que se encuentran en el cuerpo cuando padeces cáncer de páncreas: A Compendium of Potential Biomarkers of Pancreatic Cancer, publicado por PloS One. Él centró su investigación en averiguar cuál de estas proteíans podía servir como biomarcador para este tipo de cáncer. Y la encontró: la mesotelina. En una entrevista con el Dr. Francis Collins, Director de los National Institutes of Health[10]él cuenta que se encontró con que el acceso a muchos de los artículos era previo pago, normalmente $40 cada uno y que desgraciadamente muchos de ellos no los podía pagar, sobre todo cuando muchos de ellos resultaron inútiles después de leerlos. Pero en la Ted Talk él finaliza diciendo: “…a través de Internet todo es posible. Las teorías pueden ser compartidas, y no tienes que ser un profesor de universidad con múltiples titulaciones para que tus ideas sean valoradas. Es un espacio neutro, donde tu aspecto, edad o género no importa. Son sólo tus ideas lo que cuenta…Tú podrías estar cambiando el mundo. Por eso si un chico de quince años que ni siquiera sabía lo que era un páncreas, pudo encontrar una nueva manera para detectar el cáncer de páncreas, sólo imagina lo que tú podrías hacer“.

Acceso abierto quiere decir no solo acceso libre, sin restricciones e indiscriminado para el fomento del conocimiento, sino también compartir conocimiento para generar nuevo conocimiento, para avanzar y enriquecer la investigación y alcanzar una ciencia abierta.

Muchas voces autorizadas hablan sobre la inevitabilidad del acceso abierto, pero en Ciencias de la Salud, el acceso abierto no es sólo inevitable, sino sobre todo crucial porque es la salud y la vida de las personas lo que está en juego.

[1] Harnard S. The optimal and inevitable outcome for research in the online age. CILIP UPDATE, Sept 2012. p 46-8 [cited 2014 Jun 6]. Available from http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/342580/.

[2] What you can do: Budapest Open Access Initiative [Internet]. Budapest: 2002 Feb 14 [cited 2014 Jun 8]. Available from: http://www.budapestopenaccessinitiative.org/help#libraries

[3] Bethesda Statement on Open Access Publishing [Internet]. 2003 Jun 20 [cited 2014 Jun 8]. Available from http://legacy.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/bethesda.htm#libraries

[4] Kowalckzuk M. Comments on: “Are journals ready to abolish peer review?” 2014 Apr 11 [cited 2014 Jun 8]. In: Biomed Central Blog [Internet]. Available from: http://blogs.biomedcentral.com/bmcblog/2014/04/11/are-journals-ready-to-abolish-peer-review-2/

[5] Harriman S. A case for open peer review for clinical trials. 2014 Jun 4 [cited 2014 Jun 5]. In: Biomed Central Blog [Internet]. Available from: http://blogs.biomedcentral.com/bmcblog/2014/06/04/a-case-for-open-peer-review-for-clinical-trials/

[6] Willinsky J. What Is It About the Intellectual Properties of Learning?[Video]. In Opening Science to Meet Future Challenges [Internet]; 2014 March 11, Varsaw [cited 2014 Apr 22]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8za8R–9WD8

[7] http://www.copyrighthistory.com/anne5.html

[8] Véasea nota 7

[9] Andraka J. Jack Andraka: A promising test for pancreatic cancer … from a teenager . In: Ted Talk [Internet]. 2013 feb; [cited 2014 may 1]. Available from: http://www.ted.com/talks/jack_andraka_a_promising_test_for_pancreatic_cancer_from_a_teenager

[10] The Right To Research Coalition [Blog on the Internet]. Open Access Empowers 16-Year-Old Jack Andraka to Create Breakthrough Cancer Diagnostic. 2013 jun 11; [cited 2014 may 1]. Available from:http://www.righttoresearch.org/blog/open-access-empowers-16-year-old-to-create-breakth.shtml